Director: Sarah Burns and David McMahon, Ken Burns,

Watched in: Theater

Rating: 4.5/5.

The Central Park Five, directed by Ken Burns, his daughter Sarah Burns and her husband, David McMahon, is many things: an historical record of New York in the late ‘80s when it was gripped by fear and racism; a true crime thriller, recounted with incisive journalistic scrutiny; and an emotionally wrenching personal story of five boys whose lives were shattered by a heinous miscarriage of justice. It is both extremely well-crafted and intimately moving, a testimony to the power of patient, attentive storytelling.

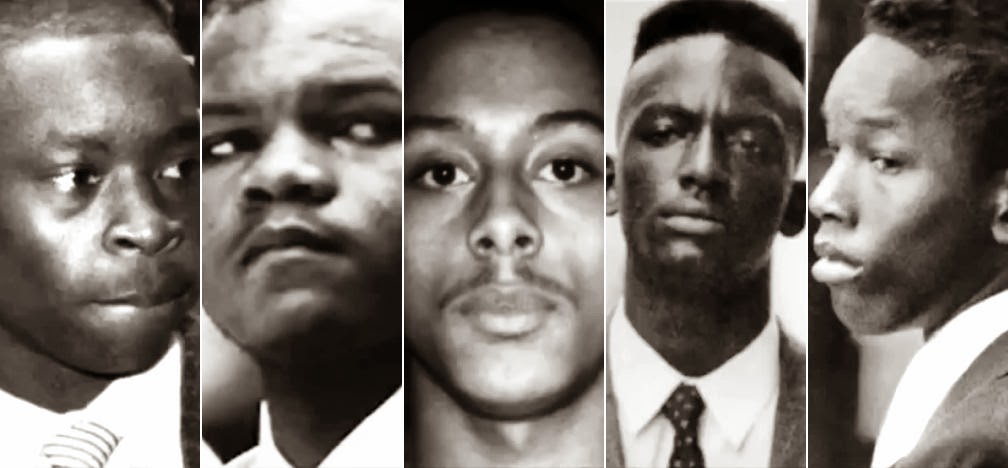

How many of us remember the story of the Central Park jogger? A young, white, Wall Street working woman who went out for an evening run in the park, and was brutally raped and beaten and left for dead in the brush. How many of us remember the five black and mixed-race teenagers arrested, convicted and jailed for the crime? The story claimed front-page space in newspapers nationwide. The party line was this: the teens were members of a so-called “wolf pack” of thugs, roaming the parks and streets of the world’s most famous city, engaging in something called “wilding”, savage and random attacks on defenseless, innocent people. The awful story of their rampage confirmed the image of New York as a crime-ridden metropolis, overrun by menacing black gangs high on crack.

In the ensuing weeks, the police, the press and even mayor Ed Koch signed, sealed and delivered the fate of the Central Park Five before their trial began. They had, after all, confessed to the crime on paper and on videotape. Even Donald Trump got into the act, taking out full-page ads for the death penalty, proving that he was sharpening his racist knives long before Barack Obama became president. But what this film shows us, in agonizing detail, is how these unfortunate young men fell into an inexorable black hole of justice wronged.

Employing a meticulous chronology composed of news footage, headlines, police videotape and current interviews with the five men, the directors of The Central Park Five show how the teens’ confessions were coerced, how details of those confessions did not match any of the physical evidence of the crimes, how actual DNA evidence of their participation did not exist and, in fact, that some evidence was withheld. The boys recanted their confessions, and stood their ground, even when offered a plea bargain for a shorter sentence. In the process, we watch five frightened boys struggle to understand how their obvious innocence was no match for the onslaught of hate, fear and sensationalism surrounding the crime.

As is typical when cops and prosecutors mishandle a crucial case and are exposed, none of them were willing to be interviewed for this film. Their crimes against the humanity of these young men remain, to this day, unpunished. Because of that, the movie is not an exoneration of the boys’ reputations; it is instead a heartbreaking chronicle of lives halted. The men recount their stories with articulate sorrow, their rage buried under tears. There is a sense they will never shake off the nightmare of what happened to them.

Based on a book by Sarah Burns, the movie may not uncover any new ground for New Yorkers familiar with the details of the case, but for the rest of us, The Central Park Five is a grim memorial to an event that echoes the Emmett Till and Scottsboro Boys tragedies. The film at times simplifies the swirl of complex forces that led to the teens’ wrongful convictions, but its concerns are human, not procedural. History is only as compelling as those who lived through it.