Director: Greg “Freddy” Camalier,

Watched on: DVD,

Rating: 3/5.

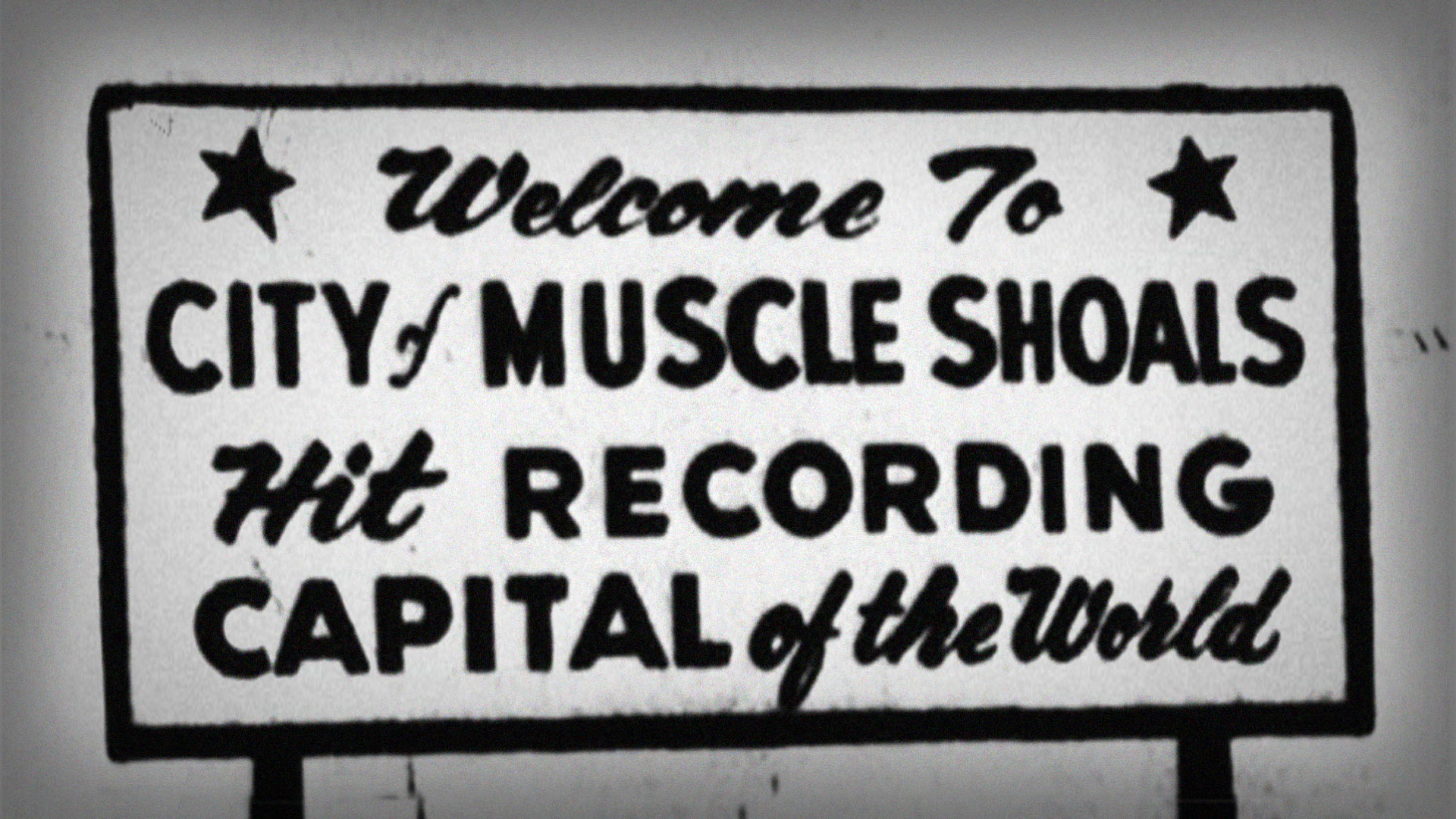

Muscle Shoals tells the story of two legendary Alabama recording studios located near the banks of the Tennessee River, “a singing river,” as the locals like to say. Music is in the water and the blood of this deeply Southern region, and those elements no doubt helped lay the fertile groundwork for some of the most memorable songs in the American canon of rock, soul and funk. Aretha Franklin, Percy Sledge, the Rolling Stones, Wilson Pickett, Clarence Carter, the Allman Brothers and Jimmy Cliff made the pilgrimage to Muscle Shoals, drawn there by a rootsy vibe that is so ineffable even this documentary struggles to define it.

A commendable effort by first-time director, Greg ‘Freddy’ Camalier, the film tells the story of FAME Studios’ founder, the mercurial Rick Hall, and his house band, The Swampers, who set out on their own to build the Muscle Shoals Sound studio, where they recorded Lynyrd Skynyrd’s classic southern rock anthem, “Free Bird.” It’s a fascinating story, one that begins with an irresistible bass and drum line, a beat so funky that black artists brought into the studio to record were astonished to learn their backing band was composed of all-white southern boys. But the music created in this Tennessee backwater jumped racial lines, and soon they produced a monster hit record for Percy Sledge, the seminal “When A Man Loves A Woman”, which kicked off a feverish rush by musicians to add that same gritty authenticity to their own records. Franklin’s “Respect”, Pickett’s “Mustang Sally”, the Stones’ “Brown Sugar”, and Clarence Carter’s number #1 smash “Patches” were all eventually recorded in Muscle Shoals.

Director Camalier has a wealth of material to work with. Black-and-white footage of early studio sessions, old photographs, plenty of interviews with surviving artists and band members, and the ever-present Rick Hall, whose backstory could make a film all by itself. With a life scarred by tragedy, obsession, alcoholism, and a relentless drive to make a mark in the world, Hall cuts an imposing figure, formidable and self-regarding.

But what exactly was his secret touch with a recording knob? What was the essence of his talent? The documentary barely nicks the surface of these questions, which makes the repeated shots of Hall posing in front of his studio, wearing a cowboy business suit and a defiant sneer, a bit tiresome. A tendency toward repetition, in fact, is this movie’s overriding albatross. Clocking in at 111 minutes, Muscle Shoals would have made a terrific impression at a much shorter length. But Camalier succumbed to obvious marketing temptations, including too many talking heads, too many dead end side trips, and too many shots of cotton fields waving in the gentle southern breeze. The photography is stunning, to be sure, but the film’s almost regal prettiness–Alabama looks like a storybook paradise–becomes the director’s go-to device when he runs out of ideas. Even the interviews with the likes of Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Aretha Franklin are framed like royal portraits, bathed in splendored light.

Despite the drawbacks, Muscle Shoals is filled with plenty of surprising revelations and a feast of musical highlights. It works as a compelling personal story, a fine tribute to an historical landmark, and a kick-ass survey of some of the best funk this country has ever produced.