Director: Amir Bar-Lev,

Watched at: True/False Film Festival,

Rating: 4.5/5.

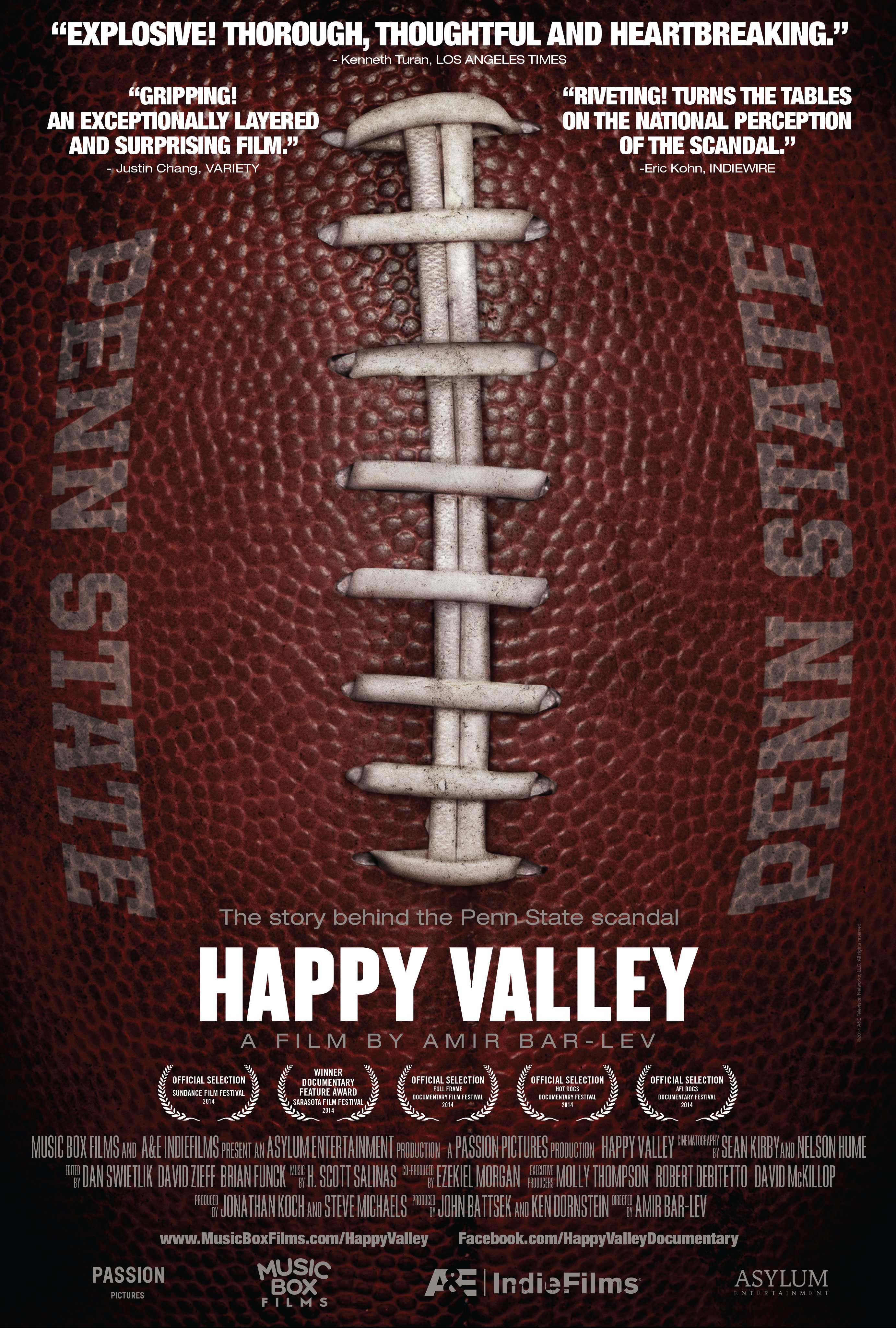

Happy Valley is filmmaker Amir Bar-Lev’s dissection of the aftermath of the Jerry Sandusky-Penn State scandal. Arriving on the scene after Sandusky, an assistant football coach to the legendary Joe Paterno, was sentenced to prison on more than forty counts of child sexual abuse, Bar-Lev turns his camera on the university, the surrounding neighborhood, the media and the culture of college football. What I assumed to be a title dreamed up by the director turns out to be the colloquial name of the area where the university resides. It’s an irony Bar-Lev confronts head-on, resulting in a multi-faceted and deeply troubling portrait of a quasi-tribal world of hero worship, secrets, cover-ups, and a peculiarly American form of idolatry.

Happy Valley raises important questions about this country’s fawning reliance on symbols, myth, and so-called community values when forced to grapple with uncomfortable truths or challenges to the status quo. To his credit, Bar-Lev doesn’t set out to answer these questions, instead employing a consistently probing, wry approach that invites us to examine our own reverence for institutions and the heroes they produce. He interviews Joe Paterno’s widow and two of her sons. He talks to a disgruntled Penn State student who sees the university’s outcry over the scandal, and their subsequent dismantling of Paterno’s legend, as nothing more than a hypocritical feint. He also interviews Jerry Sandusky’s adopted son Matt, a disillusioned but searingly honest young father who offers a damning indictment of Sandusky and the ritualized deference paid to a sport and its heroes by an anesthetized community.

Bar-Lev doesn’t stop there. He sketches a brief biography of Paterno, depicting a man who convinced himself that he, and the football team he commanded, existed on an exalted plane, where the coach’s Lombardi-like aphorisms and charitable largesse were a shield against misconduct. He also returns again and again to an intriguing setting, the town’s beloved mural that depicts Paterno and others, including Sandusky, as immortal totems of good will and benevolence. At one point a halo is added over Paterno’s head. What happens at this location, which also includes a newly installed statue of the coach, serves as a kind of Wailing Wall for fans, tourists and, in one extended scene, a lone protestor who, undaunted by aggressive Paterno apologists, literally makes a stand for the children molested by Sandusky. Bar-Lev also delves into the riot that ensued after Paterno was fired, revealing an ugly undercurrent of brainwashed loyalism in the now very unhappy community of Happy Valley.

The media gets some of the blame for destroying Paterno’s legacy, but here again Bar-Lev takes a different approach. His scenes of news trucks and cameras and stand-ups depict a profession entirely leashed to the 24/7 news cycle, forced into a reactive and reductive mindset, unable or unwilling to report with nuance, interpretation or analysis. They play the same role in Bar-Lev’s The Tillman Story, his devastating and terribly sad tale of former football star-turned-Army Ranger Pat Tillman, whose death by friendly fire in Afghanistan was covered up and exploited by the Bush Administration as a heroic emblem of America’s will to fight. Then, as now, the media dutifully reported whatever came their way.

The release of Happy Valley is aptly timed to the end of the regular college football season, when teams make a push for a major bowl invitation and holiday gatherings are routinely inundated with televised games. But for far too many, football is more than just a game, and it is more than just football. It is a religion, inextricably knotted together with money and power and celebrity. This excellent film offers incriminating evidence of the damage such an unholy alliance can lead to.