Films watched on: Kanopy,

Ratings: Titicut Follies 3/5, Boxing Gym 3/5, Ex-Libris 2.5/5, National Gallery 1.5/5, At Berkeley 1/5.

Frederick Wiseman’s approach to his chosen subject matter, the internal workings of institutions, is as unwavering as his camera. His films are long (the last four have run more than 3 hours each; At Berkeley, which had me asking for a hall pass after 15 minutes, lasted 4 hours). He shoots with available light and the crew consists of his cameraman and himself, holding the boom mic and recording sound. His films avoid talking head interviews, on-screen graphics, music, or anything more rudimentary than a tripod for getting his unobtrusive but up-close footage. He spends months editing, which is always surprising to me, since his entire approach to cutting is taught in beginning film classes: exterior establishing shot, wide shot of a group of people, medium shot on the focal point of the group, a series of cutaways of people listening or interjecting, and then another round of this approach until the next establishing shot of a new location. Rinse, repeat.

The director has many fans among film critics, but until recently, it was hard for audiences to find and watch his movies. Now, for a limited time, they are available on the streaming site Kanopy, which is free if your public library subscribes to their platform. Wiseman always finds money for his extensive forays. He could offer to make a film about paint drying and he would probably get several hundred thousand dollars to do it. In fact, he did make that film, National Gallery, which was my personal Waterloo with the Wiseman canon.

I watched all of National Gallery (well, I fast-forwarded through much of it) and swore I’d never watch another of his marathons. Then I read the effusive praise for his last film, Ex Libris, and I warily walked back through the doors. Was it worth it? I don’t know. I love public libraries (I didn’t used to) so I appreciated his catholic fondess for the durability and accessibility of one of the last surviving institutions of democracy. The movie does have an admirable scope. But there is not a single image or sequence or scrap of information I remember from it. That’s because Wiseman is not the least bit interested in cinema.

He was once, maybe a few times. His 2010 picture, Boxing Gym, is set almost entirely in a busy, scruffy neighborhood gym in Austin, Texas. We meet the owner of the joint and we glimpse several people of all ages, sexes, ethnicities and abilities working out there. We never get to know any of them. Most fade from sight after a few seconds of footage of punching a bag or jumping rope or engaging in off-hand banter with other gym members. This would all be fairly dull if it wasn’t for the editing of the repetitive motions and sounds of the gym into a trance-like music, a suggestion that the world of the gym offers a transom of escape from the mundane routines of the outside world. The details of the body-mind focus suggest a kind of church and, because of the unfussiness of Wiseman’s technique, there is no preachiness in this conceit. The film, at 91 minutes, works in the way most trances should: you get lost in it just long enough to emerge refreshed.

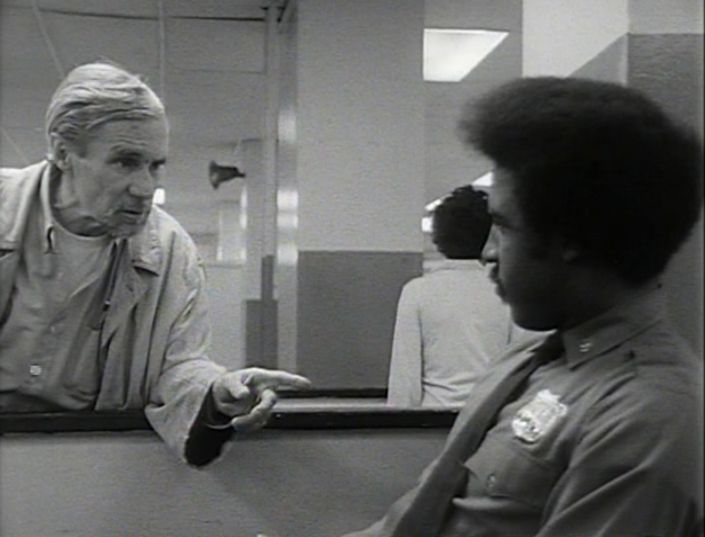

His most famous film, 1967’s Titicut Follies, is a brief and brutal exposé of life inside an asylum for the criminally insane. The movie is rough-looking. The sound clangs against your ears. The constant belittling of the guards towards the inmates, and the inmates’ heartbreaking mental health issues contribute to an oppressive atmosphere. All of the Wiseman tropes are there–no interviews, title cards, identifying names, non-diegetic music, or deep character revelations–but the movie displays an energy in the editing and a damning point-of-view that is almost non-existent in the director’s later works. In other words, the filmmaker is present in Titicut Follies, especially in a sequence that silently intercuts the preparation of a dead body for the morgue freezer into a scene of an inmate being force-fed through a tube. It might be the last truly remarkable thing Wiseman ever did with edited frames of a film.

In contrast, his movies today, from the stance of film-as-cinema, rather than film-as-a-vehicle-to-record meetings, are decidedly morgue-ready. They are no more alive than an institution’s annual report, complete with photos and quotes and the humdrum of stated goals and mission statements.

This is all really okay. Wiseman can do what he wants. But why does he keep getting valuable dollars thrown his way from the half-empty honey pots of granting organizations? Why does he show up at financing forums and allow himself to go through the agony of a pitch to broadcasters and distributors? More to the point, why do these forums let him take up the time that could be given to filmmakers they’ve never heard of? With Wiseman, after all, these industry gatekeepers know exactly what they’ll get.

Then again, that’s why they’re in the business in the first place.