Hal

Director/Amy Scott

Watched on Amazon Prime

Rating 3/5

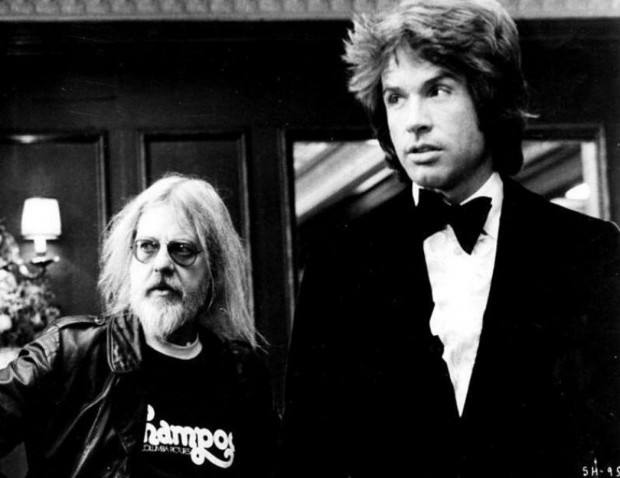

Amy Scott’s Hal suffers from the same pro forma banalities as most other celebrity or “troubled artist” documentaries. It is both overly produced and under imagined. Nothing within the film’s style, structure or point-of-view attempts to emulate or pay aesthetic respect to the actual artist it profiles, in this case Hal Ashby, the supremely talented director of The Last Detail, Shampoo, Coming Home, and Bound For Glory, among other films.

Hal charges out of the gate with a rapidly edited montage of clips, talking heads, reenactments, and the introduction of actor Ben Foster’s voice as the “voice of Hal” in a few regrettably cheesy scenes of hands clacking away at a typewriter (he was a writer, see?). I was ready to turn it off after 10 minutes. I simply couldn’t stand to suffer through another slapdash cash-and-carry of a filmmaker’s reputation like I’d witnessed in Tony Zierra’s hideous Filmworker, a movie that, through no fault of either the protagonist Leon Vitali or the work of the late Stanley Kubrick, made it seem as if they were both participating in a circa-1999 desktop documentary.

Unlike Filmworker, which I shuttered after a half-hour, I decided to stick this one out. Thankfully, director Scott had access to actual voice recordings of Ashby which, when paired with Foster’s intense readings of angry letters and passionate notes that Ashby sent to studio hacks and adoring friends, respectively, the portrait that emerges is of a man who may have been the last social justice activist who ever tried to survive and thrive within an industry that chews up iconoclasts like a 16mm chunk of celluloid jammed in a projector’s gate. Supported by interviews with his best friend and early champion Norman Jewison, actors he worked with such as Louis Gossett Jr and Beau and Jeff Bridges, and directors he influenced–Allison Anders, Judd Apatow, Lisa Cholodenko–the film, if nothing else, will inspire a much-needed revisiting of his output.

You get the feeling that everyone interviewed genuinely adored the man, and feel a perfectly righteous indignation as to how the industry stole his films out from under him, locking him out of edit suites, and treating him like a socialist infiltrator within a capitalist old boys’ club. And this despite (or maybe because of) the immense critical and commercial appeal of his work. It was at the pinnacle of Ashby’s most important career success, the still-vital and prophetic Being There, that his battles with the studios took a tragic turn. His admirers all basically agreed that the stress and anger he experienced created the cancer that eventually killed him.

It is a credit to Ashby’s integrity and artistic power that his words and his work (the film clips are generous, but there could always be more) are still even now able to overcome the predictability of the celebrity documentary form–a predictability he disdained and fought against his whole career. We can ignore the film’s perfunctory design and still be delighted and inspired by Hal Ashby’s generous gifts and bracing commitment to the arts of writing, directing, and editing film. Before he died, he was looking forward to the digital revolution, still 10 years away, when he would be able to shoot and edit movies on his own, far away from the grasping venality of the gatekeepers.