Caniba

Directors/ Lucien Castaing-Taylor, Véréna Paravel

Watched on Criterion Channel

Rating 2/5

This text below appears on the Criterion website accompanying the streaming version of Caniba:

In 1981, as a thirty-two-year-old student at the Sorbonne in Paris, Issei Sagawa was arrested when spotted emptying two bloody suitcases containing the remains of his Dutch classmate, Renée Hartevelt, whom days earlier he had killed and begun eating. Declared legally insane, Sagawa now lives as a free man in Japan, earning a living off his crime by writing novels, drawing manga, reenacting the murder for documentaries and sexploitation films, and even working as a food critic.

Apparently, the information above originally appeared in on-screen text introducing this film to festival audiences. Perhaps directors Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel felt this gave away too much information, or it somehow tainted the rigorous artistic sheen they were striving for, or maybe they just wanted to fuck with their viewers. With or without this knowledge, the experience of watching this uniquely repellent work remains the same. It is nasty, grueling, unpleasant in the extreme, and also, inexplicably hypnotic.

But with some information filled-in regarding the backstory of the film’s “star,” Issei Sagawa and his caretaker brother, Jun Sagawa, you’ll at least have a clearer picture as to how Sagawa, the titular cannibal, managed to go free after committing the murder and partial eating of Hartevelt, referred to only as “Renee” in the film. I watched the film not having read the Criterion text, but I was able to piece enough of the story together to be thoroughly repulsed anyway.

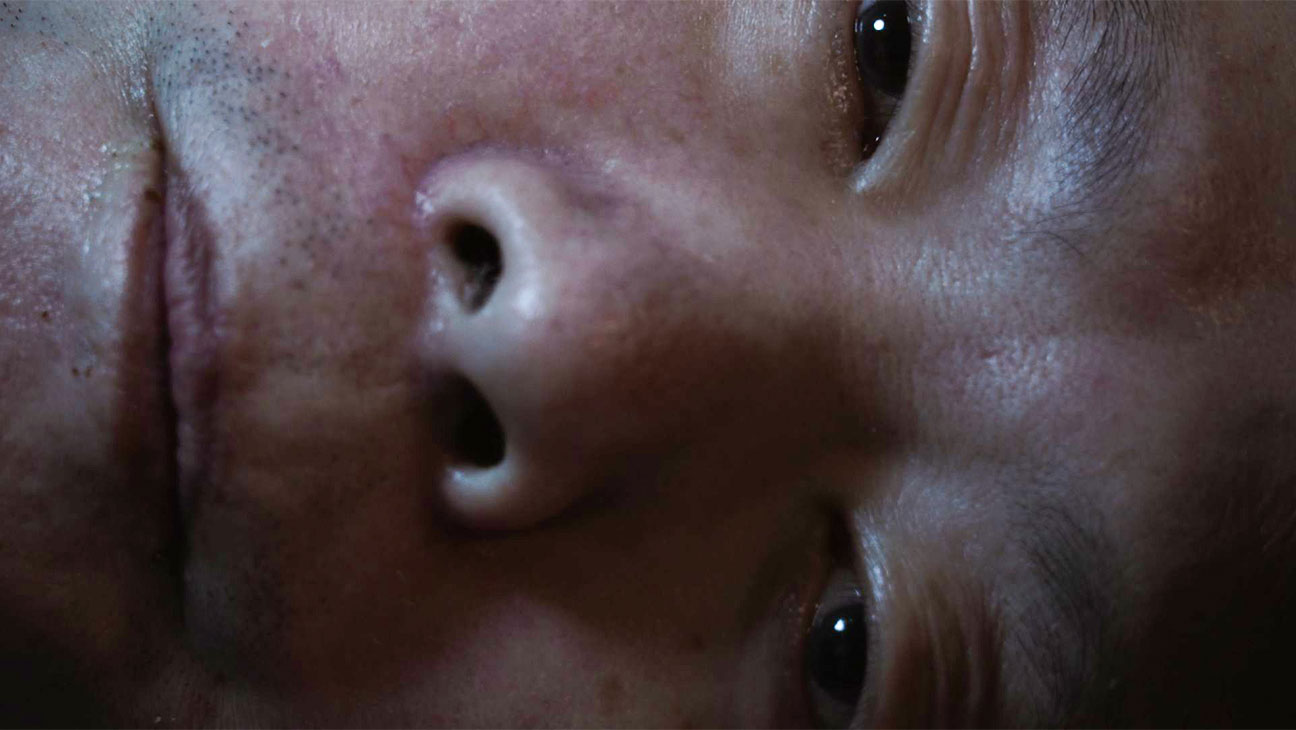

Caniba doesn’t show us any acts of cannibalism, although we do get to see and hear Sagawa slurping noodles and drinking some kind of liquid from a water bottle. Much of the film comes to us in an unremitting series of claustrophobic close-ups, granular macro images of Sagawa’s skin and sweat and the weird, slimy sheen of his facial features. The camera fixates on these details while Sagawa recounts his self-absorbed fantasies and obsessions, delivered with the skewed erudition of a sick, twisted amateur philosopher. Once the filmmakers have had enough of him, they switch the focus of the film to Jun, his brother, who, as it turns out, has some demented perversions of his own to share.

The film, shot with a lo-fi camera set on auto-focus, grainy and pixeled and not at all concerned with expectations of proper framing and composition, seems to be relentlessly calculated to ask how much a viewer is willing to endure. In that sense, Caniba skews toward pornography. Hermetic and self-satisfied, the technique employed by Castaing-Taylor and Paravel is intentionally limiting. They’ve chosen, to their credit, to avoid any attempts at normalizing or sensationalizing or even judging Sagawa’s atrocity, but by relying on a stylization so relentlessly icky, they’ve really given a viewer no way to evaluate the film. The hypnotic effect of the movie results from the one-dimensional persistence of their vision, which comes across as both nihilistic and full of shit.

Suffer through Caniba if you must, but please don’t make the mistake of thinking this is art.