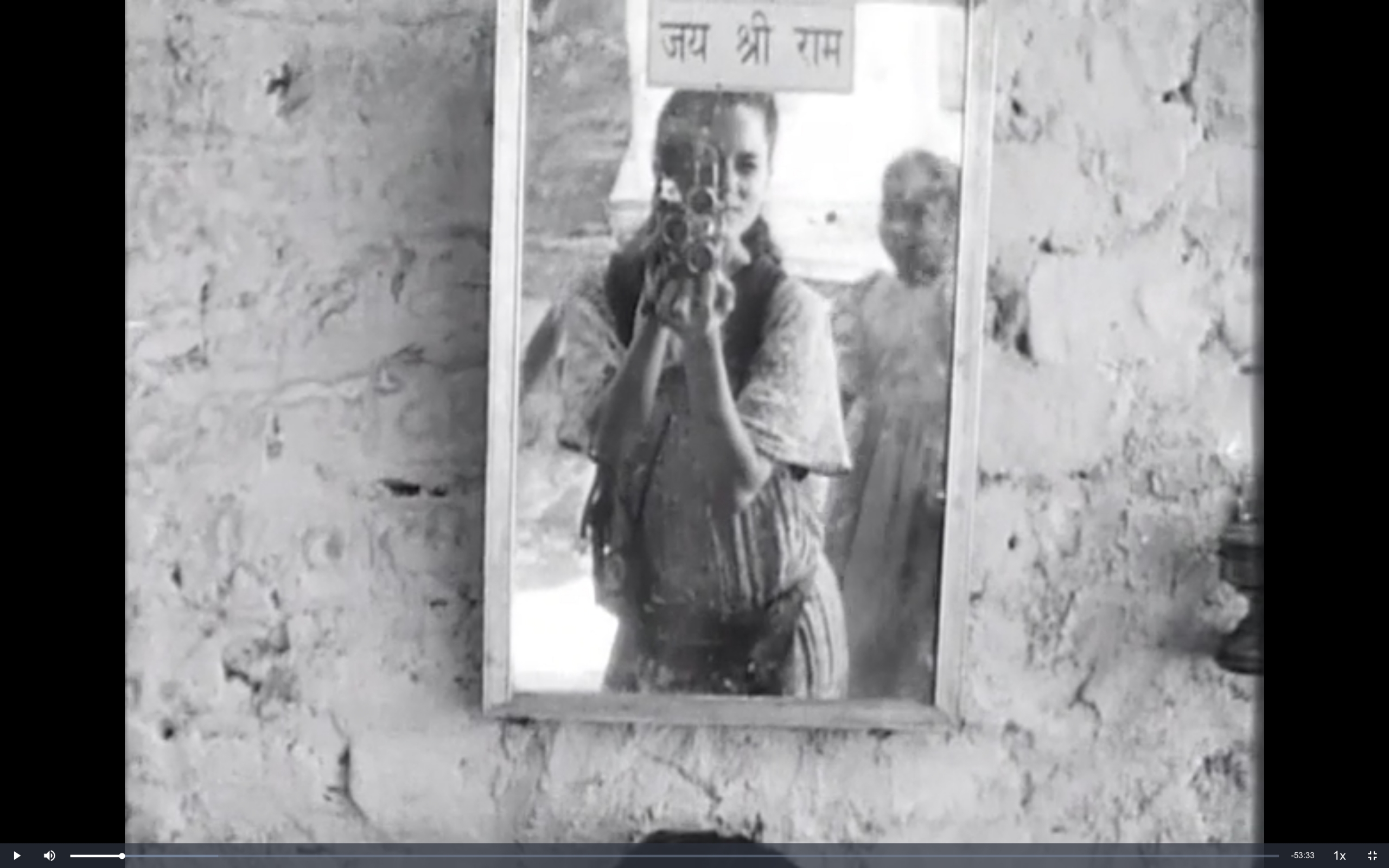

Nina Davenport filming Hello Photo (1994)

The Pandemic Future: Time for a Radical Return to Documentary’s First Golden Age

I recently wrote a book with a title that is now comically ironic. Get Close: Lean Team Documentary Filmmaking, published in February 2019 by Oxford University Press, was intended as a refreshing cri de cœur for beginning and veteran filmmakers to commit to a stripped down, low-budget, one or two-person team approach to documentary filmmaking. I emphasized personal creative expression, encouraging filmmakers to become the author of their own work from start-to-finish: directing, shooting, recording sound, writing, and editing. This, I emphasized, could only be achieved by eliminating the financial, physical and emotional barriers between the cameraperson and their characters, and by embracing an intimate storytelling style. “Get close” is the mantra the book is based on.

Absurd, right?

That’s what I thought, too. But with all of the teeth-gnashing going on in the documentary world about the tenuous future of forums, markets, festivals, and productions in either limbo or purgatory, I believe the timing is perfect for a new strategy, one that is actually grounded in the roots of the early days of the digital documentary filmmaking revolution, when cheap cameras and laptop editing software were intentionally designed for the homemade filmmaker.

“We may now be passing through a short golden age of documentary production without even being aware of it,” wrote director Chuck Braverman on the IDA website, “when the stars have aligned to allow documentaries to be produced for relatively modest budgets. If you ever wanted to produce that great doc, now may be the time.”

Braverman wrote that in 2003. Even earlier, in the 1990s, Betsy McLane, Director Emerita of the International Documentary Association, declared it was the affordability of lightweight cameras and on-board shotgun mics that signaled a nascent golden age. This accessibility, she said, “brought the power of a cut to anyone with a home computer.” I was one of those filmmakers.

I’ve been making films for twenty years, nearly all with a single production partner (my wife, Ann Hedreen) or as a one-person team, wearing all the hats from start to finish. I’ve never had a film in a major film festival, received a grant from Sundance, or successfully networked with anyone at a forum or a market. My films have screened in regional festivals, won awards, and streamed on all the platforms, but when I have managed to get face time with a gatekeeper, they usually never look me in the eye and they certainly never return my emails. In other words, I’m like the vast majority of doc filmmakers. I’m not the bride, the groom, the bridesmaid or the best man. I’m not even the usher. I’m the guy who showed up at the church but can’t get in because I’m not a family member.

As the global pandemic has changed the prospects of our personal and professional lives, it also presents a bleak prognosis for documentary filmmakers. Film festivals, forums and markets are scrambling to adapt by going virtual and production teams are wondering how and when they’ll be able to pick up where they left off. Projects with large budgets and furloughed crews are at a standstill. The current golden age of doc filmmaking, recently trumpeted by NPR, the Guardian, and the Wall Street Journal, and defined by big box-office, huge budgets, and celebrity-driven profiles, may be over.

Yes, bleak is one way to look at, but for filmmakers like myself, this is an opportunity for a great correction.

I see a future, a lean team documentary filmmaking future, in which smaller stories–filmed close to home, focusing on family members or friends; on iconoclasts or artists or anonymous heroes; on lone wolf characters with unique stories to tell–as the way forward. Stories that will illuminate something essential or provocative about the times we live in.

Films that explore challenging, demanding new narrative structures will become the norm, rather than the one-off. Essay films; docs that rely on archival or stock footage; that borrow from the public domain or a filmmaker’s private vault of old files; first-person journals and diaries; memoir films. No more experts, no more endless all-you-can-eat buffets of talking heads, no more expensive overseas location shoots, no more heavily lighted interiors, no more impact campaigns where stories suffer in the service of ticked social justice boxes, no more films about celebrity chefs and dead fashion designers, and, mercilessly, an end to the dispiriting glut of lurid true crime documentaries.

I see filmmakers learning anew or reacquainting themselves with all the skills of filmmaking–from handholding their $4,000 Sony to watching FCPX tutorials on Lynda.com to editing and exporting their rough cut–on their way to becoming self-contained and self-reliant; a one-person crew with no need to socially distance, and no need to worry about the health and safety of their sound person, their grip, their driver, their unpaid interns, and their editing assistants. With a single character, family or location thoroughly vetted and trusted, the filmmaker can work with little money and no executive oversight. They are free to experiment, to express their creative urges, to become–like the writer, the painter, the musician–a solo artist. This is how I made my last film, My Mother Was Here (Best Documentary, Audience Award, Tacoma Film Festival), filming alone, with my mom as the only character in her cluttered mobile home, working in my spare time with equipment I already owned. My budget was essentially zero. If the pandemic had been going on during that time, I could have kept shooting.

I write in my book that the playing field for doc filmmakers needs a leveling. Budgets have soared to a million dollars or more, which means a handful of films receive the lion’s share of available money, leaving everyone else to exist on labor-intensive crowdfunding. Many film festivals program the same dozen or so films each year, taking up precious slots and decreasing the chances that the unknown film will ever get a break. And filmmakers spend years and thousands of dollars traveling to forums and pitch sessions to compete against filmmakers with recognized names, a better network, and a financial cushion, often coming home with nothing.

“The big films don’t sustain the industry, it is sustained by the ‘middle’, and the middle is suffering badly,” said Cinephil’s Philippa Kowarsky last year at CPH-DOX. With money about to get a whole lot more scarce, with festivals disappearing for good, with filmmakers too broke to travel, with travel itself up in the air, there has never been a better time for change in an industry that many filmmakers decry as “broken.” It is time for the films in the middle, the under-the-radar and the under-sung, to take back the genre.

Here are a few suggestions:

Pitch sessions and forums can easily be conducted in one-on-one Zoom meetings, ending the practice of in-person seminars and roundtables, which take up a ridiculous amount of time and money and hold little value for most of those attendees.

Funders can spread the wealth. Rather than one film receiving a $100,000 grant, ten filmmakers can each receive $10,000. A filmmaker who is awarded a grant must allocate 10% of that grant to another filmmaker who was rejected. Total grants for any one film must be capped at $50,000.

Festivals, virtual or otherwise, must be up front about the number of open slots available to submitting filmmakers. They can cap the number of films they’ll accept and shorten their window for submissions, meaning chances of getting accepted will improve. Virtual festivals will have reduced budgets and staff anyway, so they won’t need to rely as heavily on entry fees.

These ideas will increase transparency and decrease the growing gap between the haves and the have-nots of the documentary world. But the most dramatic change must happen with filmmakers themselves. We have to reimagine what documentary filmmaking is. Get personal, go deep, stay light, stay lean, and even get close, but only if it’s safe. If you have to, you can still tell stories from six feet away. All of the material you need to keep making films are right around you, just like they were twenty years ago. The laptop on your desk. The camera on the shelf. The family member with the story to tell. The crusading friend. The woman living alone in a rundown house.

The documentary industry, in their insatiable need for content, will eventually have to accept new work, to listen to these new voices, these risky new storytelling strategies. They will be at the mercy of the artists, rather than the other way around.